Below is an excerpt from the report “Through The Looking Glass: Digital Safety and Internet Freedom in South and Southeast Asia” published in June 2022 by EngageMedia and the Oxen Privacy Tech Foundation (OPTF) in collaboration with the Cambodian Center for Indepedent Media (CCIM), Ranking Digital Rights (RDR), The Institute for Policy Research and Advocacy (ELSAM), Society for Peace and Democracy, Digital Rights Nepal (DRN), Out of the Box (OOTB) Media Literacy Initiative, and Hastag Generation. To view or download the full report, click this link.

FROM November 2021 to January 2022, the six country partners conducted research and produced reports on the digital safety capacity of human rights defenders and at-risk communities, as well as the internet freedom context of their countries. These reports include an assessment of popular telecommunications companies against a set of indicators that measure freedom of expression and online privacy.6

It should be noted that the research is presented for analysis by the reader. We have not included recommendations for each of the countries. A summary of the trends across the countries, along with key recommendations, can be found in the main section of this report.

This Annex contains edited versions of the six reports produced by the country partners.

THE past five years have seen a steady decline in freedom of expression. This has followed the coordinated crackdown on independent media in mid-2017, when over 30 independent radio stations were shut down by the Cambodian government.

With almost all independent media institutions eradicated, Cambodian people have been forced to rely largely on social media and other online platforms to access news and information.

The vulnerability of this reliance became apparent in early 2021, when the government issued a sub-decree to establish a National Internet Gateway (NIG) – a China-style firewall – which would create a single point of entry for all internet traffic under the government’s control. This poses a huge threat to internet freedom in Cambodia, and is yet another indication of the government’s intentions to suppress access to information and freedom of expression. Journalists, activists, and civil society organisations (CSOs) are particularly at risk, as are the vulnerable groups they support through their advocacy efforts surrounding human rights, media freedom, and democracy.

Digital Safety Capacity Analysis

In response to declining internet freedom in Cambodia, the Cambodian Center for Independent Media (CCIM) conducted an online survey of internet users, with a focus on gauging the digital safety capacity of human and environmental rights defenders, including activists, journalists, media producers, policymakers and lawyers. Survey responses were received from 34 individuals with backgrounds primarily in media and journalism (56%), human rights (23.5%) and environmental issues (15%). Of the respondents, 60% identified themselves as male, 37% identified as female, and 3% indicated that they did not want to reveal their gender.

Online Survey – Key Findings

- Use of email platforms: Gmail is by far the most popular email platform, used by 97% of respondents, while 12% of the respondents also indicated they had Outlook accounts.

- Use of messaging apps: The most popular instant messaging apps are Facebook Messenger and Telegram. Interestingly, usage of WhatApp was low, with the use of Signal being slightly higher than WhatsApp.

- Digital attacks: The digital attacks that were of most concern to respondents were account takeover, online impersonation, online surveillance, online harassment, and hate speech. In terms of actual experiences, a high percentage of respondents indicated they have been harassed or subjected to hate speech and online gender- based violence.

- Threat actors: Respondents indicated greater concern over state actors compared with non-state actors. 44% indicated they had some or high levels of concern about state actor attacks, compared to 24% expressing some concern about attacks from non-state actors and 36% indicating they had no concern about attacks from non- state actors.

- Protecting against digital attacks: Over 60% reported having low capacity to protect themselves from the digital threats and attacks they highlighted as most concerning.

- Passwords: Only 50% of respondents are confident about the strength of the passwords they use to access important devices and accounts. However, 50% of them use two-factor authentication (2FA) on all or most of their accounts, with many reporting that it is one of the digital security skills they have learned from digital safety training programs.

- Online censorship: Over 64% of respondents have faced censorship and blocks on websites and apps they wished to access to some level. Only 1% of respondents indicated having high capability to access censored or blocked content.

- Online surveillance: Only 2% of respondents indicated they have a high level of capability to browse the web anonymously using TOR or a virtual private network (VPN).

- Use of collaboration and online conference calling platforms: Zoom and Google Meet are the most used platforms. Jitsi is used by a small proportion; however 52% indicated they never use it. 33% indicated they had a low level of confidence collaborating or participating in online conferences safely and securely.

- Digital safety skills: 12% of respondents indicated having a high level of digital safety skills, with a further 59% indicating they had a medium level and 29% indicating a low level of skills.

- Digital safety training: 59% of respondents indicated having attended a digital safety training in the last 24 months.

At-risk Communities

To gain a deeper understanding of the specific vulnerabilities of at-risk communities to mounting digital threats, CCIM got in touch with youth representatives (aged between 17 and 22 years) from two at-risk communities: a group of indigenous people in Ratanakiri province, and a group of university students in Siem Reap province.

Indigenous communities

Indigenous people in Cambodia are particularly vulnerable to online discrimination and attacks for three primary reasons:

- Lack of sufficient education around social media and digital skills;

- Lack of reliable, easily accessible, and comprehensible sources of information;

- Their marginalised ethnic identity.

When asked to describe the level of ICT skill that their community has, responses from all nine of the young indigenous people interviewed ranged from “zero” to “poor”. They also all reported that, despite being more likely to fall victim to digital attacks, indigenous people seem not to be interested in learning tips that might improve their digital safety. While this was unanimously agreed upon, none of the interviewees were able to pinpoint the reason why this is the case.

Specific challenges reported anecdotally by the interviewees include being invited to join inappropriate or offensive Facebook groups, forgetting account passwords, social media accounts being hacked, and a general inability to use many phone applications properly.

The younger generation of indigenous people is in a better position than their elders in terms of digital safety, thanks to the proliferation of digital and media literacy trainings aimed at young people from CSOs, such as the Cambodian Youth Network (CYN) and Transparency International Cambodia (TI-Cambodia), and environmental activists. Still, interviewees declared that more specific training on using social media safely and responsibly are required. They also expressed a desire to learn how to use media as part of their freedom of expression advocacy efforts, reporting that many young people in the area are interested in producing videos and writing news reports using their smartphones.

University students

Facebook hackings, sexual messages, and cyber bullying are the three most critical digital concerns for university students, according to the nine individuals involved in this focus group discussion. These threats were thought to primarily come from friends on social media, strangers, scammers, and internet service providers.

Actual experiences of attacks reported by interviewees include requests by strangers for private information, impersonation, suspicious links, and requests to join dodgy chat rooms. All of these have the potential to be extremely dangerous.

Respondents suggested that university students are particularly vulnerable to digital threats and attacks for a range of reasons, including a lack of understanding and critical thinking, habits and behaviours surrounding social media, the society or community they live in, and poor ICT skills – which were reported as ranging from “low” to “medium”.

The primary reason given for such low skills and a lack of willingness to improve them was that university students simply do not care about their digital safety. For example, an informant indicated that if a student’s social media account is hacked or taken over by strangers, they will simply create a new account.

When issues do arise, most university students tend to turn to someone who they think might be able to deal with them (i.e., friends with better ICT skills than their own).

All nine of the university students interviewed had, at some point, attended a training on media literacy. All students reported being very interested in attending more training programs on this topic, in particular to learn about online safety and privacy, digital security, information verification, photography and photo-editing skills, and how to counter cyber bullying, hate speech, and sexting.

Telecommunications Companies Policy Analysis

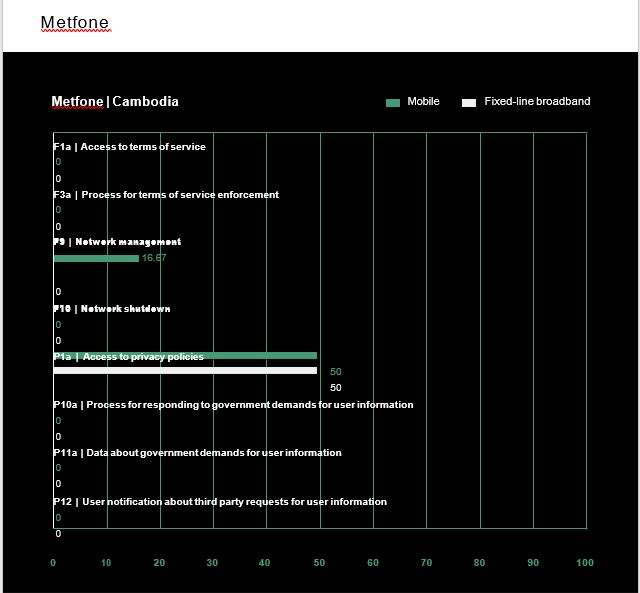

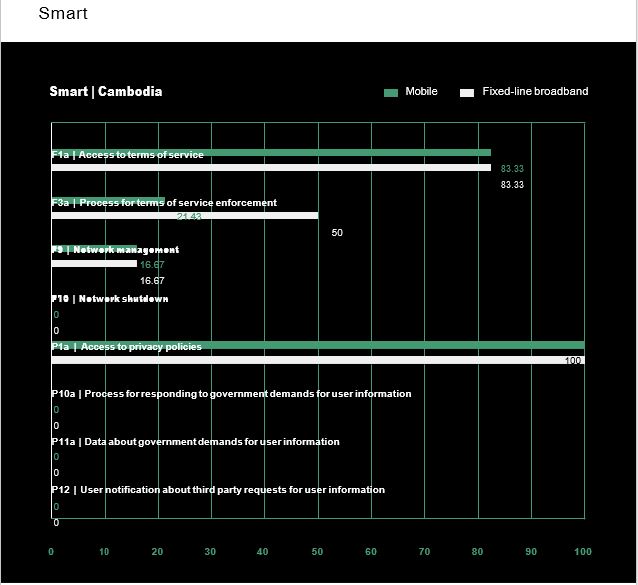

The two charts below are generated from data associated with the RDR indicators used in this research. The indicators measure the publicly available policies of the telecommunications companies in relation to freedom of expression and privacy. Please refer to Annex 2 for more information about the RDR indicators and the scoring process, or visit https://rankingdigitalrights.org/2020-indicators.

Key takeaways

- Metfone does not have a Terms of Service policy that could be accessed; however, a short and broad Privacy Policy could be found only in English rather than in Khmer language for local people in Cambodia to read and understand.

- Since the disclosure of public policies in relation to Terms of Use is not available on the company’s website, there is no information on how the company acts on government requests to flag content. Without mentioning clear processes on how the company will respond to such requests, Metfone has room to manoeuvre in response to government requests to shut down or block internet services.

- The company claims it will not pass private information about its users to third parties, including government authorities. However, the policies related to the proposed National Internet Gateway will enable the government to have full access to private information about all internet users in Cambodia.

Key takeaways

- Smart Axiata’s Terms and Conditions are easy to find on its website and are available in both English and Khmer. However, it is difficult to understand due to the technical and legal terms used in presenting terms of services. It should also be noted that the Terms and Conditions state: “The English version will prevail over any translation. The Subscriber acknowledges that it has had the opportunity to review a Khmer translation of the GTCs or to go to Smart website.”

- Privacy policies are easy to find on its website. The privacy policies are available in both English and Khmer and written in an understandable manner. In section 5 of the Privacy Policy, titled ‘Disclosure of Personal Data’, the company states: “We keep your personal data confidential and do not share it with any third party or government authority, except under the following circumstances: a) to meet our legal and regulatory obligations, including to prevent and/or detect crime; b) to enforce and/or safeguard our rights, usage terms, intellectual/physical property, our safety or of associated parties; c) if we are acquired by or merged with any other company; or d) for any legal claim, where we are required to do so.” However, the policy does not include information about the process the company follows to respond to non-judicial government demands or court orders. Equally important, there is no disclosure found related to international data transfer. In section 6 of the Privacy Policy, titled ‘Cross Border Data Transfer’, the company states: “We do not sell, trade, transfer or otherwise share your personal data, except: (…) b) as required by law, such as in conjunction with government inquiry, litigation or similar legal processes. However, the policy does not include information about the process that the company follows to respond to government demands from foreign jurisdictions.” Within this context, it is still possible that the company might pass the private information of its Internet subscribers to the government if required to do so.

- It should be noted that Smart will also be required to comply with the proposed government’s National Internet Gateway policies, and in this context, user information will be directly accessible by government authorities.

Trends and Concerns for Reviewed Telecommunications Companies in Cambodia

- Linguistic accessibility of terms and conditions for reviewed companies can still be improved further, to ensure that users from all backgrounds can fully understand the fine print of the terms.

- While in varying levels, both companies reviewed can also work on improving disclosures on how they protect their users’ privacy and data, especially amid

- concerns about government authorities requesting access to user data. It is imperative for the companies to clearly and thoroughly state their privacy policies and stances related to key privacy concerns so users can be fully aware of this when they use the companies’ services.

- The impact of the government’s internet gateway policies on the telecommunications companies’ policies is of major concern for civil society. Further research can be done on how the companies’ disclosures and action will be affected by the government’s internet gateway policies as time goes by.

Internet Freedom Context

Cambodia’s internet freedom will be severely impacted when the NIG is implemented. The NIG not only enables authorities to control internet access and impose censorship, but will also assist in monitoring users and their online behaviour. Needless to say, it will have a detrimental impact on independent journalists, activists, and civil society organisations working on human rights, good governance, and democracy.

Even without a centralised NIG, there is ample evidence that there are tight controls over internet activities by government authorities. In March 2020, Cambodia’s Ministry of Information established a Fake News Monitoring Committee that had the power to monitor social media as well as “block websites, accounts, or pages that promote false information that cause social unrest”.7 In April 2020, the government used the COVID-19 crisis as cover to pass laws that would give them the ability to censor the media.8 During the same month, the popular online news channel TVFB was blocked and its editor-in-chief arrested for allegedly inciting social disorder after he shared comments made by the country’s Prime Minister on informal workers and their hardships.9

There is no doubt that the proliferation of hate speech is a massive problem in the country. Research by Licadho indicates that the government itself is “one of the most visible perpetrators of online harassment” in the country.10 Laws related to ‘fake news’ have been weaponised against journalists and government critics, with Human Rights Watch documenting 30 arbitrary arrests in early 2020.11

The power and control over internet freedom that the NIG will give the government is deeply concerning, especially in the context of general elections earmarked for 2023. Critical voices are already restricted, and if the public are fearful that their online conversations can be easily monitored, there will be little debate or discussion about the future direction of Cambodia.

8 https://rsf.org/en/cambodia-hun-sen-uses-covid-19-crisis-tighten-his-grip

9 https://vodenglish.news/news-site-blocked-journalist-jailed-after-quoting-hun-sen/

10 https://www.licadho-cambodia.org/reports.php?perm=235

11 https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/29/cambodia-covid-19-spurs-bogus-fake-news-arrests