The rise of social media and mobile internet have drastically changed traditional media and communication, enabling information access and dissemination at the speed of light over free and open platforms.

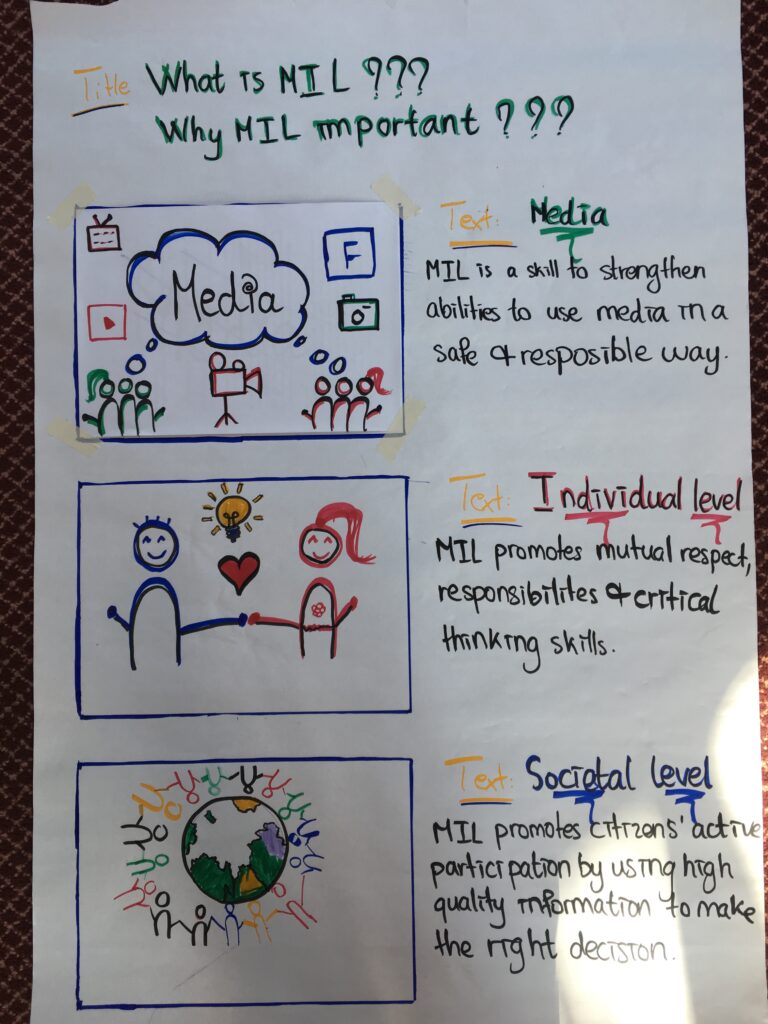

The Cambodian government took an important step in 2016 by adding Media and Information Literacy (MIL) to the national high school curriculum. UNESCO defines the programme as a knowledge and skill set enabling students to access, evaluate and use media products “to transform people’s interaction with information” online and beyond the internet.

Given the constant evolution of the digital space, governments need the input of educational organisations and training programmes to help students and others keep up with the changes and ensure there is widespread understanding of the digital world.

MIL did not make its way into Cambodian high schools by chance. The curriculum’s introduction highlighted important values taking shape in the country’s fast-changing media landscape. The addition was the product of a long, joint effort between the Ministry of Education, Youths and Sport of Cambodia (MoEYS) and DW Akademie, a journalism training organisation based in Germany. The initiative also benefited from partnerships with civil society groups including the Women’s Media Center of Cambodia and the Cambodian Center for Independent Media (CCIM).

Social media helps transform information consumers into content creators. Posting and sharing comments, images and videos have become common daily activities. Yet the diversity of information fueled by high-speed communication has a dark side. Misinformation, disinformation, mal-information, conspiracy theories, racial and gender discrimination, hate speech and cybercrime have become critical digital challenges to the public and social stability. Information overload undermines the ability of social media users to think, analyze and judge rationally.

MIL has played a critical role in promoting media and digital literacy, but not everyone can benefit from this important education effort. The current scope of the initiative is relatively small, giving those who live in cities greater access to the programmes than rural residents.

The programme also is only available to Grade 12 students, leaving out those below the age of 17 despite being active social media users. Women and youths from marginalised communities, who have left formal education, also have fewer chances to gain media literacy training or understand its safe and responsible use. This creates digital dilemmas, including difficulty distinguishing between facts and opinions or accurate information and false narratives. The inability to fully comprehend an increasingly mainstream digital media landscape increases their vulnerability.

While there is no single strategy to address these difficulties manufactured by the modern information era, looking to the past successes of MIL could be the best route for navigating toward a better future.

CCIM established two groups in 2018 called Media Club 101 at Paññāsāstra University of Cambodia and University of Puthisastra, which provided a training curriculum jointly developed by CCIM and DW Akademie.

Information overload undermines the ability of social media users to think, analyse and judge rationally

These media training programmes have equipped Cambodian students with the means to develop critical thinking skills and apply their creativity to advocacy and knowledge sharing. The approach is garnering international accolades for participants.

Students Cheam Sethi, Ly Vanika and Chhouk Chanthida took fourth place in a 2019 video contest organised by the German Embassy and German political education foundation Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Another Cambodian student, Chhorn Porseng, earned second place in a 2020 competition hosted by Voice for Gender Equality, a project funded by the EU.

A regional conference organised by DW Akademie and UNESCO Bangkok brought together youths from Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar to discuss MIL practices and challenges.

“By attending the conference, I learnt a lot of MIL skills from the people coming from different countries with different backgrounds,” said Heng Rachana, a member of Media 101 Club at Paññāsāstra University of Cambodia.

In the last five years, media literacy training has yielded scores of satisfactory outcomes. Yet the limited scope of the programmes remains a critical obstacle preventing this important learning opportunity from generating a widespread impact on Cambodian society.

Addressing this challenge requires not only stronger political involvement and cooperation from agencies and individuals interested in education, but also more resources, time and investment in media literacy training.

Media and Information Literacy needs more support throughout Southeast Asia. Increasing the scope and access to this education is a vital component in enabling students who speak disparate tongues away from their computers and mobile devices to learn how to interpret the universal language of the digital world.

Source: Southeast Asia Globe