Bordering Preah Sihanouk province’s Veal Rinh district and located some 30 kilometers west of Kampot town, Prek Tnoat and Trapaing Ropov are two coastal fishing communities situated in Prek Tnoat commune and are among the total of nine coastal fishing communities in Teuk Chhou district, Kampot province.

Villagers in the two fishing communities claim that fishing in the sea provides them with income for a reasonable living, but a development project invested in by a private firm owned by a former senator from the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has sparked concerns for their future.

Trapaing Ropov fishing community was formed in 2002 and formally recognized by the royal government in 2009. It covers a total of 1,251 hectares of sea water and the two villages of Trapaing Ropov and Prek Kreng.

Prek Tnoat fishing community was formed in 2002 and formally recognized by the royal government in 2011. The community covers 1,168 hectares of sea with the area rich in mangroves.

Mr. Uon Rima, 46, a Cham fisherman from the Prek Tnoat fishing community, says he and his parents have been fishing for a living since he was a young kid, and fishing earns him an average income of 50,000 Riels to 120,000 Riels a day.

The income generated from fishing has enabled Rima to build a house – the 8-meter wide by roughly 12-meters long concrete structure is worth around US$30,000.

“We borrowed US$5,000 from the bank in addition to our savings. We count on the daily fishing for the income we use to pay it back once a month. In a day, we earn between 50,000 to 60,000 Riels or sometimes even 100,000 Riels, and we save some for the loan repayment. We got the loan to repay, and then we got a house,” Rima says.

Another villager in the Prek Tnoat fishing community who also fishes for a living, Mrs. Yem Sok Phea says her husband can earn between 100,000 and 200,000 Riels (between US$25 and US$50) a day, and some days, he earns up to 500,000 Riels (roughly US$125) from fishing with a net.

This fishing livelihood, she adds, has improved the living conditions of her family, allowing them to be able to enjoy a similar way of life to other villagers in the community.

“I built my house and this comes from the fishing in the sea,” Sok Phea says.

Mr. Sok Chennea has been buying sea food from the villagers for many years and people call him a ‘middleman.’ The middleman says he collects roughly 100 kilograms of seafood products a day from the villagers, but the amount decreases to just 50 kilograms following the arrival of the rainy season.

He buys shrimps from the villagers at 40,000 Riels (US$10) per kilogram during public holidays and at 30,000 Riels per kilogram on normal days. For squid, Chennea says he buys from the fishermen at 30,000 Riels per kilogram.

“Seafood are sold at the door of my house sometimes, and sometimes I go out to buy more myself, leaving my wife to get seafood brought at my house. I also have fishing equipment, and I can earn more money from 50,000 to 60,000 riels from fishing. The amount of profit I get from seafood trading is depend on whether the seafood is still alive or frozen. For alive seafood, I can make profit from 3,000 to 5,000 riels per kilogram,” Sok Chennear said.

Mr. Tith Rin, leader of the Trapaing Ropov fishing community says some 70% of the total population of 1,170 households in Trapaing Ropov and Prek Kreng villages fish for their living.

“If the coastal area land filling happens, various types of ecological livings such as seagrasses, corals, mangroves, and family fishing will be impacted. We have gone fishing around the coastal area since our ancestors, and if the coastal area land filling happens, what will we do? Income we earn from fishing is to mainly support our children education and then no one take migration on the other hand,” Tith Rin said.

The leader of Prek Tnoat fishing community Mr. Ouk Sovanrith, meanwhile, says that between 75% to 80% of the community’s more than 300 households also depend on sea fishing.

Although the number of fishing community members is smaller than that of the total households living in the community, Mr. Ouk Sovanrith adds, the sea space designated for the fishing community provides both direct and indirect benefits to all villagers.

According to a report on the organization of the fishing communities, there are many different varieties of biodiversity in the sea spaces designated for both fishing communities including 500 hectares of sea grass, seaweeds, coral and mangroves, which are the habitats for sea species such as shrimp, crab, fish, squid, snails, oysters and so on.

‘Ching Kor’ Firm Pushes for Investment Project that Encroaches on Fishing Communities

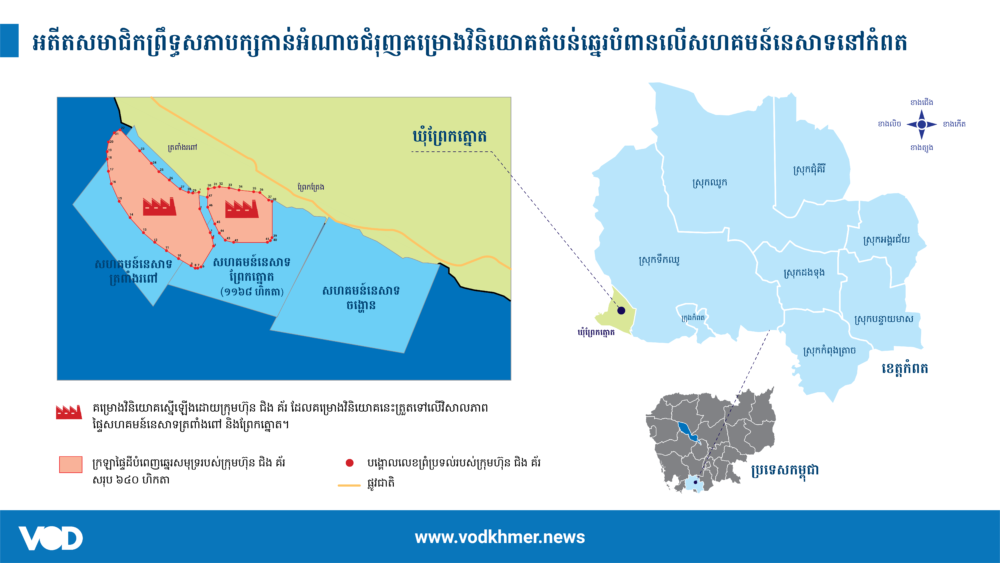

Both fishing communities have been included in an investment proposal to develop the area into a seaport, resort hub and special economic zone, which was put forward by Ching Kor Import & Export Co., Ltd., in September 2012.

According to the Ministry of Commerce’s registry, this private firm belongs to Mrs. Keo Maly, a former senator from the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) from 2012 to 2018, and a vice president of the Cambodia Chamber of Commerce.

Ching Kor has, on a number of occasions, submitted letters to the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC), the office of the council of Ministers, the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction, and the Provincial Administration of Kampot to request permission to dredge soil to fill 640 hectares of the coast located in Trapaing Ropov and Prek Kreng villages, Prek Tnoat commune, to develop the area to build a seaport and a special economic zone.

The company has made the request for land filling to expand its land area of 30 hectares it already owns and invested in building an international rice mill and a seaport since 2017.

However, the map attached with the proposal submitted to the Ministry of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction in September 2012 shows that the company asked to fill the coastal area in Block A and Block B for a total combined area of up to 1,000 hectares.

Khmer-Cham fisherman Mr. Les Loh from Trapaing Ropov village says both fishing communities will be totally wiped out if the request for land filling of the coast by Ching Kor company was to be approved by the government and the authorities.

“The land size of the community is 1,251 hectares. So, the size of the area the company is taking is 640 hectares, but if you look at the entire area of 1,251 hectares, the area is all gone. So, fishermen cannot go fishing anymore,” Les Loh says.

The chief of Prek Tnoat commune, Mr. Kong Bunra, says local authorities do not have the right to decide whether or not the investment will be permitted, but, he adds, as of now, all relevant parties are assessing the impact first.

“We held one public forum with the villagers, but the company has yet to start its investment project,” says the commune chief.

In late July this year, Mrs. Keo Maly submitted a letter to request support from the provincial governor of Kampot for its proposed investment project to move forward faster. She said the request was made because the villagers had already agreed to let the company invest by relocating the communities.

The leader of Trapaing Ropov community, Mr. Tith Rin, denied Mrs. Keo Maly’s claim. He says that only 20 to 30 villagers and the local authorities have thumb-printed on the agreement, and they, he adds, do not represent the fishing community.

Mr. Rin adds that the people who agreed have been bought.

“No one agreed, but as I said earlier, we were suppressed and prohibited by local authority. On the other hand, Chheang Vonn was brought in to intimidate the villagers. Thus, we did not know what to do; we did whatever to excuse and there were no villager participating in public forums,” Tith Rin said.

The Cambodian People’s Party lawmaker Chheang Vun rejects the allegation, saying his present with Ms. Keo Maly in forums at the communities was his private vacation.

The lawmaker acknowledges that he participated and listened to meeting between community representatives and Ching Kor’s representative, but he said he had never involved in the investment made by Ms. Maly there.

“If she is willing to the investment as what I heard in her meeting with villagers and what she signed and agreed with villagers, I am too happy. That’s what I listened to what she talked with a ministry too,” Chheang Vun said.

However, Mrs. Keo Maly claims that her company has not forced any villagers to give thumbprints. She says those who agreed were present at the consultative meeting in July 2019, and that they all agreed voluntarily.

Mrs. Keo Maly says, “There are only a small handful of people who incite others on the pretext that the people do not agree. May we ask? If the people do not agree, where do I get these thumbprints from? I have asked them to thumbprint by themselves. I have them thumbprint in my presence, and I take pictures. If they deny having thumb-printed, call the police from the interior ministry to check.”

A Prakas (ministerial order) of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery issued in April 2019 on the formation of the sea fishery management zones in Kampot province states that the regulation is intended for protection, conservation and sustainable use of sea fishery resources.

Agriculture Minister H.E Veng Sakhon says that the ministry has initiated the formations of fishing communities in the coastal areas to contribute to the sea conservation, but that he has only known about the investment project of Ching Kor company recently.

The minister adds that his ministry does not have any means to prevent that development and that he could only approve. He adds he, also, does not want to challenge.

“It’s already approved. They are the environmentalists; they are the land managers and they see it as development. So, they push for the development. But, for me, I don’t know what to say. For me, if it is already approved, I can only facilitate it. Just do whatever you are asked to do,” says Minister Veng Sakhon.

According to a report of the National Committee for Management and Development of Coastal Areas issued in January 2019, all forms of land management along the coastal areas are prohibited.

The report reads that land adjoining the coast, land adjoining the arm of the sea, land adjoining streams and waterways connecting with the sea are considered to be protected by the authorities in the coastal areas.

The Minister of Land Management, Urban Planning and Construction, H.E Chea Sophara, said he was busy when asked why the ministry decided to give the investment rights to Ching Kor company to fill in soil on the coast.

“I am a little bit busy. Ask others. I am busy,” Minister Chea Sophara says.

According to Agriculture Minister H.E Veng Sakhon, the investment right was given to Ching Kor to fill in the sea by the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC). He adds that the Ministry of Agriculture only has the right to implement the existing letter issued by the relevant ministries.

VOD has requested in writing to CDC officials for comment, but there has been no response by the publishing date of this article.

Fishermen are against the development project of the former ruling party senator

Mrs. Keo Maly claims that her company has already received an investment license for the development of this coastal area, and that the company will begin its development work soon after the environmental and social impact assessment is completed.

The former ruling party senator says the development work has been slow due to a technical study being conducted for the building of a navigational channel to avoid causing any impact on the biodiversity in the sea.

Mrs. Keo Maly says, “The government pushes us to do it every day, and we have to think carefully. How a study is conducted; how a dam is built to avoid causing the water to become turbid. We must be sure because we love our nation, not just lip-service love.”

However, the leader of Prek Tnoat fishing community, Mr. Ouk Sovanrith, says the villagers have never learned of any information on any environmental and social impact assessment.

As of now, he adds, the villagers have met with the company only two times through community public forms, but the community representative says in both of the forums, the villagers did not agree to let the company develop their area.

Mr. Ouk Sovanrith says, “Fishermen in the community do not agree. There have been two public forums so far. The villagers say they don’t allow development or landfilling in their communities.”

According to the investment plan of the company seen by VOD, Ching Kor company has requested to invest in the development project called, “Great Sea of Tourism Kampot” with an investment of over US$1,500 million for a period of 50 years.

Mrs. Keo Maly claims that her company’s investment project aims to create jobs for the locals and improve people’s economic conditions to contribute to poverty reduction in line with the Royal Government’s policies.

Mrs. Keo Maly told VOD that, “I want to do it very soon in order to give my people jobs and high salaries. I am Khmer. I want our Khmer people to have money. I want people to become rich, and their children go to school and after school, they have jobs. And when my company receives foreign investors and we cooperate with multinational investors, people in the local areas will have high salaries and have jobs.”

Villagers in the two fishing communities oppose the development project saying they are concerned that their income from fishing would decrease and their living conditions be affected in the future.

Mr. Ouk Sovanrith says Ching Kor company of Mrs. Keo Maly has tried to carry out activities on two occasions with the intention of occupying the sea spaces of both fishing communities, but the fishermen protested those activities by the workers of the company.

The community representative adds that workers from Ching Kor company first deployed buoys on the sea spaces in the area in 2015, and, for the second time, in 2018 following the elections, but the activities to enclose the sea space by the company were halted when the villagers protested.

Fisherman from Trapaing Ropov village, Mr. Sok Mouch says not only the people’s living conditions are affected, but the biodiversity in the sea including fish and shrimps are also at risk of being depleted if the project to land-fill the sea to develop it as a resort does happen.

Mr. Sok Mouch says, “It is difficult if they land-fill the sea. There will be no fish. And if the sea space is land-filled, three years later, we are not sure if there will be fish remaining. There will be the smell of soil and with soil flowing into the sea, the fish will decrease; fish won’t come near. Sea fish are different from fresh water fish. For freshwater fish like snakehead fish, when we landfill, they still come. Seawater fish, if we landfill, and they smell soil, they run away. They don’t come.”

Mr. Leuy Sokhon, a member of the network committee of the Prek Tnoat fishing community, says if the company’s project goes ahead, the villagers will not know what to do. He adds, most of the villagers who live along the coast totally depend on fishing and only 10% of them work as teachers, factory workers and government civil servants.

Mr. Sokhon says they will not work for the company because the salaries are low and they don’t have time to rest like when they are fishing. Moreover, he believes that some elderly people will not be accepted by the company for work. These are the reasons why Mr. Leuy Sokhon says the villagers will not agree to give the sea spaces they use for fishing to the company.

Mr. Leuy Sokhon says, “Even the salary is lower than what we can earn ourselves or earn by being the servant of our wives. Being a servant of your wife, you go if you want to, and if you don’t want to go, you take one day or two days of rest, there’s no problem. No-one will cut money from you. For instance, elderly people; they can go find snails or other sea species to do their living. For example, if they find two kilograms of snails, they earn 50,000 riels. Elderly people like me who are over 60 years old, who will accept us to work? Maybe, they don’t even allow us to walk near them.”

The head of the advocacy network committee of Trapaing Ropov fishing community, Mrs. Pon Nhu, warns that the villagers will migrate to work afar, especially in other countries if the plan to land-fill the sea spaces belonging to the communities does happen.

Mrs. Pon Nhu says, “I say that only fishing can help our people, and it is our Khmer culture that we have the sea, we have the coast, we have sea species, we have mangroves for helping all of us. If we allow others to land-fill [sea spaces], we don’t know what we will count on for survival. We will have to leave villages to work in other countries and we will leave our villages behind.”

Mr. Pel Kosal, Vice Governor of Kampot province, says as of now, the company has yet to start any investment activities. He adds that all relevant parties including the company and authorities are studying impacts and consulting with the villagers first.

Mr. Kosal says the impact study focuses on legality to make it conform with the decision of the Council for the Development of Cambodia. The investment project, he adds, must be in conformity with the laws and that people must also benefit from this investment project.

“The company has yet to start its development. It’s the case that the company has all necessary legal paperwork, but the ministry and the company are looking further at legal procedures in order to avoid problems,” says the vice governor.

The officer at human rights organization ADHOC in Kampot province, Mr. Yun Phally, says if the government and the company could find another location for this development project other than this sea space, it will be better.

Mr. Phally says in this area of sea space, if it is given for investment, it will affect seagrass, corals, biodiversity, seaweed, and mangroves.

“Villagers who do family-style fishing, they can only do this in the areas with shallow seawater, and if we landfill the shallow water coast, and ask them to go deep in the sea, they will lose their livelihoods,” he adds.

The Prakas of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery issued in April 2019 on the formations of sea fishery management zones in Kampot province states that the regulation is intended for protection, conservation and sustainable use of sea fishery resources.

Moreover, it is also intended to improve the living conditions of the people. In the Prakas, the Ministry of Agriculture sets out the following key goals: 1) Fishery conservation area where the ministry designates nearly 700 hectares of sea space for this purpose; 2) Fishery protection area with a size of over 3,000 hectares (3,092 hectares); 3) Fishery safety habitats, which include a total area of 16 hectares; 4) Seabed locations for ecotourism, which include 74 hectares; and 5) Fishing communities: there are three designated fishing communities, which cover more than 4,000 hectares of sea spaces (4,358 hectares).

Another Prakas of the government issued in February 2012 demarcates the coastal zones. The Prakas reads that what is considered coastline is from the line of highest tide of the seawater when it rises until the prohibited line.

In this regard, the Prakas states that any investment is prohibited including occupying or construction in the form of concrete or sand on the areas designated for public use zones and as public land of the state. At the same time, the coastal slopes are determined to be at least 30 meters from the line of highest tide towards the land.

(This report is written by Mam Moniroth contracted under the project of CCIM supported by Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung)